The Personal Website of Mark W. Dawson

Thoughts of Michael Crichton

Michael Crichton was an American author and filmmaker. His books have sold over 200 million copies worldwide, and over a dozen have been adapted into films. His literary works heavily feature technology and are usually within the science fiction, techno-thriller, and medical fiction genres. His novels often explore technology and failures of human interaction with it, especially resulting in catastrophes with biotechnology. Many of his novels have medical or scientific underpinnings, reflecting his medical training and scientific background.

Consensus Science

The following quote of Michael Crichton succinctly points out the oxymoron of “consensus science”:

“I want to pause here and talk about this notion of consensus,

and the rise of what has been called consensus science. I regard

consensus science as an extremely pernicious development that

ought to be stopped cold in its tracks. Historically, the claim of

consensus has been the first refuge of scoundrels; it is a way to

avoid debate by claiming that the matter is already settled.

Whenever you hear the consensus of scientists agrees on something

or other, reach for your wallet, because you're being had.

Let's be clear: the work of science has nothing whatever to do

with consensus. Consensus is the business of politics. Science, on

the contrary, requires only one investigator who happens to be

right, which means that he or she has results that are verifiable

by reference to the real world. In science consensus is

irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results. The greatest

scientists in history are great precisely because they broke with

the consensus.

There is no such thing as consensus science. If it's consensus, it

isn't science. If it's science, it isn't consensus. Period.”

- Michael Crichton

Environmentalism as Religion

Commonwealth Club, San Francisco, CA I September 15, 2003

This was not the first discussion of environmentalism as a religion, but it caught on and was widely quoted. Michael explains why religious approaches to the environment are inappropriate and cause damage to the natural world they intend to protect.

I have been asked to talk about what I consider the most important challenge facing mankind, and I have a fundamental answer. The greatest challenge facing mankind is the challenge of distinguishing reality from fantasy, truth from propaganda. Perceiving the truth has always been a challenge to mankind, but in the information age (or as I think of it, the disinformation age) it takes on a special urgency and importance.

We must daily decide whether the threats we face are real, whether the solutions we are offered will do any good, whether the problems we’re told exist are in fact real problems, or non-problems. Every one of us has a sense of the world, and we all know that this sense is in part given to us by what other people and society tell us; in part generated by our emotional state, which we project outward; and in part by our genuine perceptions of reality. In short, our struggle to determine what is true is the struggle to decide which of our perceptions are genuine, and which are false because they are handed down, or sold to us, or generated by our own hopes and fears.

As an example of this challenge, I want to talk today about environmentalism. And in order not to be misunderstood, I want it perfectly clear that I believe it is incumbent on us to conduct our lives in a way that takes into account all the consequences of our actions, including the consequences to other people, and the consequences to the environment. I believe it is important to act in ways that are sympathetic to the environment, and I believe this will always be a need, carrying into the future. I believe the world has genuine problems and I believe it can and should be improved. But I also think that deciding what constitutes responsible action is immensely difficult, and the consequences of our actions are often difficult to know in advance. I think our past record of environmental action is discouraging, to put it mildly, because even our best intended efforts often go awry. But I think we do not recognize our past failures, and face them squarely. And I think I know why.

I studied anthropology in college, and one of the things I learned was that certain human social structures always reappear. They can’t be eliminated from society. One of those structures is religion. Today it is said we live in a secular society in which many people—the best people, the most enlightened people—do not believe in any religion. But I think that you cannot eliminate religion from the psyche of mankind. If you suppress it in one form, it merely re-emerges in another form. You cannot believe in God, but you still have to believe in something that gives meaning to your life, and shapes your sense of the world. Such a belief is religious.

Today, one of the most powerful religions in the Western World is environmentalism. Environmentalism seems to be the religion of choice for urban atheists. Why do I say it’s a religion? Well, just look at the beliefs. If you look carefully, you see that environmentalism is in fact a perfect 21st century remapping of traditional Judeo-Christian beliefs and myths.

There’s an initial Eden, a paradise, a state of grace and unity with nature, there’s a fall from grace into a state of pollution as a result of eating from the tree of knowledge, and as a result of our actions there is a judgment day coming for us all. We are all energy sinners, doomed to die, unless we seek salvation, which is now called sustainability. Sustainability is salvation in the church of the environment. Just as organic food is its communion, that pesticide-free wafer that the right people with the right beliefs, imbibe.

Eden, the fall of man, the loss of grace, the coming doomsday—these are deeply held mythic structures. They are profoundly conservative beliefs. They may even be hard-wired in the brain, for all I know. I certainly don’t want to talk anybody out of them, as I don’t want to talk anybody out of a belief that Jesus Christ is the son of God who rose from the dead. But the reason I don’t want to talk anybody out of these beliefs is that I know that I can’t talk anybody out of them. These are not facts that can be argued. These are issues of faith.

And so it is, sadly, with environmentalism. Increasingly it seems facts aren’t necessary, because the tenets of environmentalism are all about belief. It’s about whether you are going to be a sinner, or saved. Whether you are going to be one of the people on the side of salvation, or on the side of doom. Whether you are going to be one of us, or one of them.

Am I exaggerating to make a point? I am afraid not. Because we know a lot more about the world than we did forty or fifty years ago. And what we know now is not so supportive of certain core environmental myths, yet the myths do not die. Let’s examine some of those beliefs.

There is no Eden. There never was. What was that Eden of the wonderful mythic past? Is it the time when infant mortality was 80%, when four children in five died of disease before the age of five? When one woman in six died in childbirth? When the average lifespan was 40, as it was in America a century ago. When plagues swept across the planet, killing millions in a stroke. Was it when millions starved to death? Is that when it was Eden?

And what about indigenous peoples, living in a state of harmony with the Eden-like environment? Well, they never did. On this continent, the newly arrived people who crossed the land bridge almost immediately set about wiping out hundreds of species of large animals, and they did this several thousand years before the white man showed up, to accelerate the process. And what was the condition of life? Loving, peaceful, harmonious? Hardly: the early peoples of the New World lived in a state of constant warfare. Generations of hatred, tribal hatreds, constant battles. The warlike tribes of this continent are famous: the Comanche, Sioux, Apache, Mohawk, Aztecs, Toltec, Incas. Some of them practiced infanticide, and human sacrifice. And those tribes that were not fiercely warlike were exterminated, or learned to build their villages high in the cliffs to attain some measure of safety.

How about the human condition in the rest of the world? The Maori of New Zealand committed massacres regularly. The dyaks of Borneo were headhunters. The Polynesians, living in an environment as close to paradise as one can imagine, fought constantly, and created a society so hideously restrictive that you could lose your life if you stepped in the footprint of a chief. It was the Polynesians who gave us the very concept of taboo, as well as the word itself. The noble savage is a fantasy, and it was never true. That anyone still believes it, 200 years after Rousseau, shows the tenacity of religious myths, their ability to hang on in the face of centuries of factual contradiction.

There was even an academic movement, during the latter 20th century, that claimed that cannibalism was a white man’s invention to demonize the indigenous peoples. (Only academics could fight such a battle.) It was some thirty years before professors finally agreed that yes, cannibalism does indeed occur among human beings. Meanwhile, all during this time New Guinea highlanders in the 20th century continued to eat the brains of their enemies until they were finally made to understand that they risked kuru, a fatal neurological disease, when they did so.

More recently still the gentle Tasaday of the Philippines turned out to be a publicity stunt, a nonexistent tribe. And African pygmies have one of the highest murder rates on the planet.

In short, the romantic view of the natural world as a blissful Eden is only held by people who have no actual experience of nature. People who live in nature are not romantic about it at all. They may hold spiritual beliefs about the world around them, they may have a sense of the unity of nature or the aliveness of all things, but they still kill the animals and uproot the plants in order to eat, to live. If they don’t, they will die.

And if you, even now, put yourself in nature even for a matter of days, you will quickly be disabused of all your romantic fantasies. Take a trek through the jungles of Borneo, and in short order you will have festering sores on your skin, you’ll have bugs all over your body, biting in your hair, crawling up your nose and into your ears, you’ll have infections and sickness and if you’re not with somebody who knows what they’re doing, you’ll quickly starve to death. But chances are that even in the jungles of Borneo you won’t experience nature so directly, because you will have covered your entire body with DEET and you will be doing everything you can to keep those bugs off you.

The truth is, almost nobody wants to experience real nature. What people want is to spend a week or two in a cabin in the woods, with screens on the windows. They want a simplified life for a while, without all their stuff. Or a nice river rafting trip for a few days, with somebody else doing the cooking. Nobody wants to go back to nature in any real way, and nobody does. It’s all talk-and as the years go on, and the world population grows increasingly urban, it’s uninformed talk. Farmers know what they’re talking about. City people don’t. It’s all fantasy.

One way to measure the prevalence of fantasy is to note the number of people who die because they haven’t the least knowledge of how nature really is. They stand beside wild animals, like buffalo, for a picture and get trampled to death; they climb a mountain in dicey weather without proper gear, and freeze to death. They drown in the surf on holiday because they can’t conceive the real power of what we blithely call “the force of nature.” They have seen the ocean. But they haven’t been in it.

The television generation expects nature to act the way they want it to be. They think all life experiences can be tivo-ed. The notion that the natural world obeys its own rules and doesn’t give a damn about your expectations comes as a massive shock. Well-to-do, educated people in an urban environment experience the ability to fashion their daily lives as they wish. They buy clothes that suit their taste, and decorate their apartments as they wish. Within limits, they can contrive a daily urban world that pleases them.

But the natural world is not so malleable. On the contrary, it will demand that you adapt to it-and if you don’t, you die. It is a harsh, powerful, and unforgiving world, that most urban westerners have never experienced.

Many years ago I was trekking in the Karakorum mountains of northern Pakistan, when my group came to a river that we had to cross. It was a glacial river, freezing cold, and it was running very fast, but it wasn’t deep—maybe three feet at most. My guide set out ropes for people to hold as they crossed the river, and everybody proceeded, one at a time, with extreme care. I asked the guide what was the big deal about crossing a three-foot river. He said, well, supposing you fell and suffered a compound fracture. We were now four days trek from the last big town, where there was a radio. Even if the guide went back double time to get help, it’d still be at least three days before he could return with a helicopter. If a helicopter were available at all. And in three days, I’d probably be dead from my injuries. So that was why everybody was crossing carefully. Because out in nature a little slip could be deadly.

But let’s return to religion. If Eden is a fantasy that never existed, and mankind wasn’t ever noble and kind and loving, if we didn’t fall from grace, then what about the rest of the religious tenets? What about salvation, sustainability, and judgment day? What about the coming environmental doom from fossil fuels and global warming, if we all don’t get down on our knees and conserve every day?

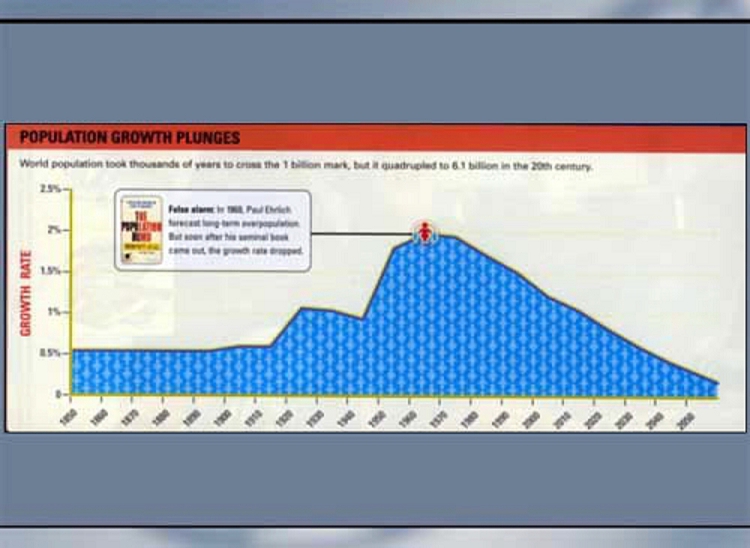

Well, it’s interesting. You may have noticed that something has been left off the doomsday list, lately. Although the preachers of environmentalism have been yelling about population for fifty years, over the last decade world population seems to be taking an unexpected turn. Fertility rates are falling almost everywhere. As a result, over the course of my lifetime the thoughtful predictions for total world population have gone from a high of 20 billion, to 15 billion, to 11 billion (which was the UN estimate around 1990) to now 9 billion, and soon, perhaps less. There are some who think that world population will peak in 2050 and then start to decline. There are some who predict we will have fewer people in 2100 than we do today. Is this a reason to rejoice, to say halleluiah? Certainly not. Without a pause, we now hear about the coming crisis of world economy from a shrinking population. We hear about the impending crisis of an aging population. Nobody anywhere will say that the core fears expressed for most of my life have turned out not to be true. As we have moved into the future, these doomsday visions vanished, like a mirage in the desert. They were never there–though they still appear, in the future. As mirages do.

Okay, so, the preachers made a mistake. They got one prediction wrong; they’re human. So what. Unfortunately, it’s not just one prediction. It’s a whole slew of them. We are running out of oil. We are running out of all natural resources. Paul Ehrlich: 60 million Americans will die of starvation in the 1980s. Forty thousand species become extinct every year. Half of all species on the planet will be extinct by 2000. And on and on and on.

With so many past failures, you might think that environmental predictions would become more cautious. But not if it’s a religion. Remember, the nut on the sidewalk carrying the placard that predicts the end of the world doesn’t quit when the world doesn’t end on the day he expects. He just changes his placard, sets a new doomsday date, and goes back to walking the streets. One of the defining features of religion is that your beliefs are not troubled by facts, because they have nothing to do with facts.

So I can tell you some facts. I know you haven’t read any of what I am about to tell you in the newspaper, because newspapers literally don’t report them. I can tell you that DDT is not a carcinogen and did not cause birds to die and should never have been banned. I can tell you that the people who banned it knew that it wasn’t carcinogenic and banned it anyway. I can tell you that the DDT ban has caused the deaths of tens of millions of poor people, mostly children, whose deaths are directly attributable to a callous, technologically advanced western society that promoted the new cause of environmentalism by pushing a fantasy about a pesticide, and thus irrevocably harmed the third world. Banning DDT is one of the most disgraceful episodes in the twentieth century history of America. We knew better, and we did it anyway, and we let people around the world die and didn’t give a damn.

I can tell you that second hand smoke is not a health hazard to anyone and never was, and the EPA has always known it. I can tell you that the evidence for global warming is far weaker than its proponents would ever admit. I can tell you the percentage the US land area that is taken by urbanization, including cities and roads, is 5%. I can tell you that the Sahara desert is shrinking, and the total ice of Antarctica is increasing. I can tell you that a blueribbon panel in Science magazine concluded that there is no known technology that will enable us to halt the rise of carbon dioxide in the 21st century. Not wind, not solar, not even nuclear. The panel concluded a totally new technology-like nuclear fusion-was necessary, otherwise nothing could be done and in the meantime all efforts would be a waste of time. They said that when the UN IPCC reports stated alternative technologies existed that could control greenhouse gases, the UN was wrong.

I can, with a lot of time, give you the factual basis for these views, and I can cite the appropriate journal articles not in whacko magazines, but in the most prestigious science journals, such as Science and Nature. But such references probably won’t impact more than a handful of you, because the beliefs of a religion are not dependent on facts, but rather are matters of faith. Unshakeable belief.

Most of us have had some experience interacting with religious fundamentalists, and we understand that one of the problems with fundamentalists is that they have no perspective on themselves. They never recognize that their way of thinking is just one of many other possible ways of thinking, which may be equally useful or good. On the contrary, they believe their way is the right way, everyone else is wrong; they are in the business of salvation, and they want to help you to see things the right way. They want to help you be saved. They are totally rigid and totally uninterested in opposing points of view. In our modern complex world, fundamentalism is dangerous because of its rigidity and its imperviousness to other ideas.

I want to argue that it is now time for us to make a major shift in our thinking about the environment, similar to the shift that occurred around the first Earth Day in 1970, when this awareness was first heightened. But this time around, we need to get environmentalism out of the sphere of religion. We need to stop the mythic fantasies, and we need to stop the doomsday predictions. We need to start doing hard science instead.

There are two reasons why I think we all need to get rid of the religion of environmentalism.

First, we need an environmental movement, and such a movement is not very effective if it is conducted as a religion. We know from history that religions tend to kill people, and environmentalism has already killed somewhere between 10-30 million people since the 1970s. It’s not a good record.

Environmentalism needs to be absolutely based in objective and verifiable science, it needs to be rational, and it needs to be flexible. And it needs to be apolitical. To mix environmental concerns with the frantic fantasies that people have about one political party or another is to miss the cold truth—that there is very little difference between the parties, except a difference in pandering rhetoric. The effort to promote effective legislation for the environment is not helped by thinking that the Democrats will save us and the Republicans won’t. Political history is more complicated than that. Never forget which president started the EPA: Richard Nixon. And never forget which president sold federal oil leases, allowing oil drilling in Santa Barbara: Lyndon Johnson. So get politics out of your thinking about the environment.

The second reason to abandon environmental religion is more pressing. Religions think they know it all, but the unhappy truth of the environment is that we are dealing with incredibly complex, evolving systems, and we usually are not certain how best to proceed. Those who are certain are demonstrating their personality type, or their belief system, not the state of their knowledge. Our record in the past, for example managing national parks, is humiliating. Our fifty-year effort at forest-fire suppression is a well-intentioned disaster from which our forests will never recover. We need to be humble, deeply humble, in the face of what we are trying to accomplish. We need to be trying various methods of accomplishing things. We need to be open-minded about assessing results of our efforts, and we need to be flexible about balancing needs. Religions are good at none of these things.

How will we manage to get environmentalism out of the clutches of religion, and back to a scientific discipline? There’s a simple answer: we must institute far more stringent requirements for what constitutes knowledge in the environmental realm. I am thoroughly sick of politicized so-called facts that simply aren’t true. It isn’t that these “facts” are exaggerations of an underlying truth. Nor is it that certain organizations are spinning their case to present it in the strongest way. Not at all—what more and more groups are doing is putting out is lies, pure and simple. Falsehoods that they know to be false.

This trend began with the DDT campaign, and it persists to this day. At this moment, the EPA is hopelessly politicized. In the wake of Carol Browner, it is probably better to shut it down and start over. What we need is a new organization much closer to the FDA. We need an organization that will be ruthless about acquiring verifiable results, that will fund identical research projects to more than one group, and that will make everybody in this field get honest fast.

Because in the end, science offers us the only way out of politics. And if we allow science to become politicized, then we are lost. We will enter the Internet version of the dark ages, an era of shifting fears and wild prejudices, transmitted to people who don’t know any better. That’s not a good future for the human race. That’s our past. So it’s time to abandon the religion of environmentalism, and return to the science of environmentalism, and base our public policy decisions firmly on that.

Thank you very much.

The Case for Skepticism on Global Warming

National Press Club Washington DC I January 25, 2005

Michael's detailed explanation of why he criticizes global warming scenarios. Using published UN data, he reviews why claims for catastrophic warming arouse doubt; why reducing CO2 is vastly more difficult than we are being told; and why we are morally unjustified to spend vast sums on this speculative issue when around the world people are dying of starvation and disease.

To be in Washington tonight reminds me that the only person to ever offer me a job in Washington was Daniel Patrick Moynihan. That was thirty years ago, and he was working for Nixon at the time. Moynihan was a hero of mine, the exemplar of an intellectual engaged in public policy. What I admired was that he confronted every issue according to the data and not a belief system. Moynihan could work for both Democratic and Republican presidents. He took a lot of flack for his analyses but he was more often right than wrong.

Moynihan was a Democrat, and I’m a political agnostic. I was also raised in a scientific tradition that regarded politics as inferior: If you weren’t bright enough to do science, you could go into politics. I retain that prejudice today. I also come from an older and tougher tradition that regards science as the business of testing theories with measured data from the outside world. Untestable hypotheses are not science but rather something else.

We are going to talk about the environment, so I should tell you I am the child of a mother who 60 years ago insisted on organic food, recycling, and energy efficiency long before people had terms for those ideas. She drove refrigerator salesmen mad. And over the years, I have recycled my trash, installed solar panels and low flow appliances, driven diesel cars, and used cloth diapers on my child—all approved ideas at the time.

I still believe that environmental awareness is desperately important.

The environment is our shared life support system, it is what we pass on to the next generation, and how we act today has consequences—potentially serious consequences—for future generations. But I have also come to believe that our conventional wisdom is wrongheaded, unscientific, badly out of date, and damaging to the environment. Yellowstone National Park has raw sewage seeping out of the ground. We must be doing something wrong.

In my view, our approach to global warming exemplifies everything that is wrong with our approach to the environment. We are basing our decisions on speculation, not evidence. Proponents are pressing their views with more PR than scientific data. Indeed, we have allowed the whole issue to be politicized—red vs blue, Republican vs Democrat. This is in my view absurd. Data aren’t political. Data are data. Politics leads you in the direction of a belief. Data, if you follow them, lead you to truth.

When I was a student in the 1950s, like many kids I noticed that Africa seemed to fit nicely into South America. Were they once connected? I asked my teacher, who said that that this apparent fit was just an accident, and the continents did not move. I had trouble with that, unaware that people had been having trouble with it ever since Francis Bacon noticed the same thing back in 1620. A German named Wegener had made a more modern case for it in 1912. But still, my teacher said no.

By the time I was in college ten years later, it was recognized that continents did indeed move, and had done so for most of Earth’s history. Continental drift and plate tectonics were born. The teacher was wrong.

Now, jump ahead to the 1970s. Gerald Ford is president, Saigon falls, Hoffa disappears, and in climate science, evidence points to catastrophic cooling and a new Ice age.

Such fears had been building for many years. In the first Earth Day in 1970, UC Davis’s Kenneth Watt said, “If present trends continue, the world will be about four degrees colder in 1990, but eleven degrees colder by the year 2000. This is about twice what it would take to put us In an ice age.” International Wildlife warned “a new ice age must now stand alongside nuclear war” as a threat to mankind. Science Digest said “we must prepare for the next ice age.” The Christian Science Monitor noted that armadillos had moved out of Nebraska because it was too cold, glaciers had begun to advance, and growing seasons had shortened around the world. Newsweek reported “ominous signs” of a “fundamental change in the world’s weather.”

But in fact, every one of these statements was wrong. Fears of an ice age had vanished within five years, to be replaced by fears of global warming. These fears were heightened because population was exploding. By 1995, it was 5.7 billion, up 10% in the last five years.

Back in the 90s, if someone said to you, “This population explosion is overstated. In the next hundred years, population will actually decline.” That would contradict what all the environmental groups were saying, what the UN was saying. You would regard such a statement as outrageous.

More or less as you would regard a statement by someone in 2005 that global warming has been overstated.

But in fact, we now know that the hypothetical person in 1995 was right. And we know that there was strong evidence that this was the case going back for twenty years. We just weren’t told about that contradictory evidence, because the conventional wisdom, awesome in its power, kept it from us.

(This is a graph from Wired magazine showing rate of fertility decline over the last 50 years.)

I mention these examples because in my experience, we all tend to put a lot of faith in science. We believe what we’re told. My father suffered a life filled with margarine, before he died of a heart attack anyway. Others of us have stuffed our colons with fiber to ward off cancer, only to learn later that it was all a waste of time, and fiber.

When I wrote Jurassic Park, I worried that people would reject the idea of creating a dinosaur as absurd. Nobody did, not even scientists. It was reported to me that a Harvard geneticist, one of the first to read the book, slammed it shut when he finished and announced, “It can be done!” Which was missing the point. Soon after, a Congressman announced he was introducing legislation to ban research leading to the creation of a dinosaur. I held my breath, but my hopes were dashed. Someone whispered in his ear that it couldn't be done.

But even so, the belief lingers. Reporters would ask me, “When you were doing research on Jurassic Park, did you visit real biotech labs?” No, I said, why would I? They didn’t know how to make a dinosaur. And they don’t.

So we all tend to give science credence, even when it is not warranted. I will show you many examples of unwarranted credence tonight. But here’s an example to begin. This is the famous Drake equation from the 1960s to estimate the number of advanced civilizations in the galaxy.

N=N* fp ne fl fi fc fL

Where N is the number of stars in the Milky Way galaxy; fp is the fraction with planets; ne is the number of planets per star capable of Supporting life; fl is the fraction of planets where life evolves; fi is the fraction where intelligent life evolves; and fc is the fraction that communicates; and fL is the fraction of the planet’s life during which the communicating civilizations live.

The problem with this equation is that none of the terms can be known. As a result, the Drake equation can have any value from “billions and billions” to zero. An expression that can mean anything means nothing. The mathematical appearance Is deceptive. In scientific terms—by which I mean testable hypotheses—the Drake equation is really meaninglessness.

And here’s another example. Most people just read it and nod:

“How Many Species Exist? The question takes on increasing Significance as plants and animals vanish before scientists can even identify them.”

Now, wait a minute... How could you know something vanished before you identified it? If you didn’t know it existed, you wouldn’t have any way to know it was gone. Would you? In fact, the statement is nonsense. If you were never married you’d never know if your wife left you.

Okay. With this as a preparation, let’s turn to the evidence, both graphic and verbal, for global warming. As most of you have heard many times, the consensus of climate scientists believes in global warming. Historically, the claim of consensus has been the first refuge of scoundrels; it is a way to avoid debate by claiming that the matter is already settled. Whenever you hear the consensus of scientists agrees on something or other, reach for your wallet, because you're being had.

Let’s be clear: the work of science has nothing whatever to do with consensus. Consensus is the business of politics. Science, on the contrary, requires only one investigator who happens to be right, which means that he or she has results that are verifiable by reference to the real world. In science, consensus Is irrelevant. What is relevant is reproducible results. The greatest scientists in history are great precisely because they broke with the consensus.

And furthermore, the consensus of scientists has frequently been wrong. As they were wrong when they believed, earlier in my lifetime, that the continents did not move. So we must remember the immortal words of Mark Twain, who said, “Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.”

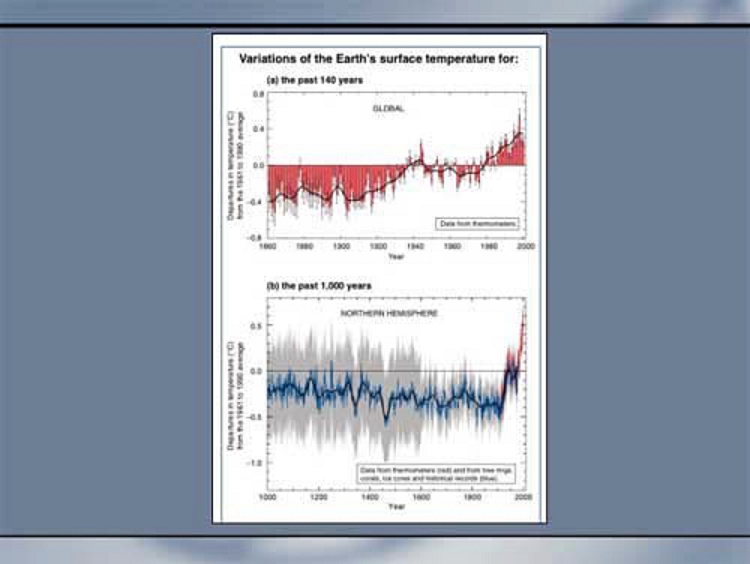

So let’s look at global warming. We start with the summary for policymakers, which is what everybody reads. We will go into more detail in a minute, but for now, we assume the summary has all the important stuff, and turning to page three we find what are arguably the two most important graphs in climate science in 2001.

The top graph is taken from the Hadley Center in England, and shows global surface warming. The bottom graph is from an American research team headed by Mann and shows temperature for the last thousand years.

Of these two graphs, one Is entirely discredited and the other is seriously disputed. Let’s begin with the top graph.

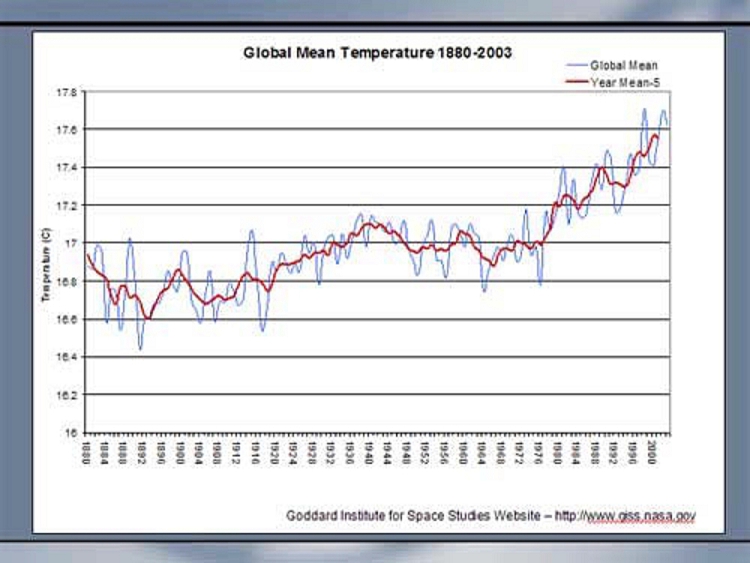

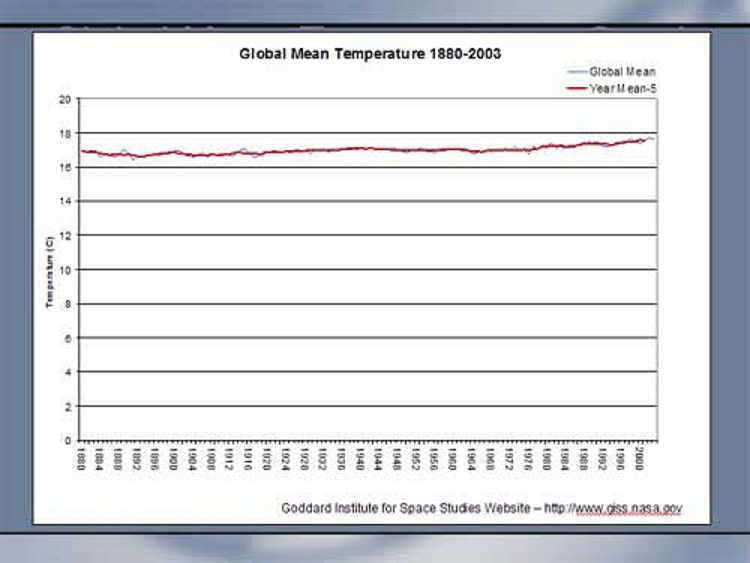

I have redrawn the graph in Excel, and it looks like this.

Now the first thing to say is that there is some uncertainty about how much warming has really occurred. The IPCC says the 20th century temperatures increase is between .4 and .8 degrees. The Goddard Institute says it is between .5 and .75 degrees. That’s a fair degree of uncertainty about how much warming has already occurred.

But let’s take the graph as given. It shows a warming of .4 degrees until 1940, which precedes major industrialization and so may or may not be a largely natural process. Then from 1940 to 1970, temperatures fell. That was the reason for the global cooling scare, and the fears that it was never going to get warm again. Since then, temperatures have gone up, as you see here. They have risen in association with carbon dioxide levels. And the core of the claim of CO2 driven warming Is based on this thirty-five year record.

But we must remember that this graph really shows annual variations in the average surface temperature of the earth over time. That total average temperature is ballpark sixteen degrees. So if we graph the entire average fluctuation, it looks like this:

So all the interest is in this little fluttering on the surface. Let’s be clear that I am graphing the data in a way that minimizes it. But the earlier graph maximizes it. If you put a ball bearing under a microscope it will look like the surface of the moon. But it is smooth to the touch. Both things are true. Question is which is important.

Since I think the evidence is weak, I urge you to bear this second graph in mind.

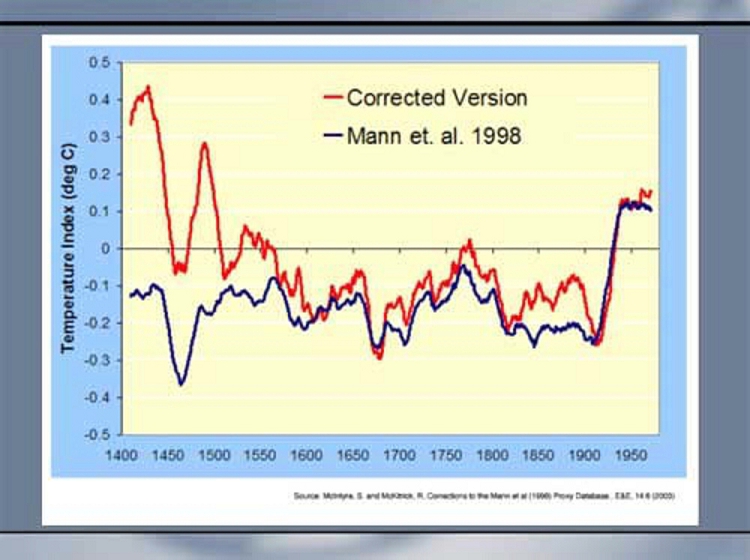

Now the question is, is this twentieth-century temperature rise extraordinary? For that we must turn to the second graph by Michael Mann, which is known as the “hockey stick.”

This graph shows the results of a study of 112 so-called proxy Studies: tree rings, isotopes in ice, and other markers of relative temperature. Obviously there were no thermometers back in the year 1000, so proxies are needed to get some idea of past warmth. Mann’s findings were a centerpiece of the last UN study, and they were the basis for the claim that the twentieth century showed the steepest temperature rise of the last thousand years. That was said in 2001. No one would say it now. Mann’s work has come under attack from several laboratories around the world. Two Canadian investigators, McKitrick and McIntyre, re-did the study using Mann’s data and methods, and found dozens of errors, including two data series with exactly the same data for a number of years. Not surprisingly, when they corrected all the errors, they came up with Sharply differing results.

But still this increase is steep and unusual, isn’t it? Well, no, because actually you can’t trust it. It turns out that Mann and his associates used a non-standard formula to analyze his data, and this particular formula will turn anything into a hockey stick---including trendless data generated by computer.

Physicist Richard Muller called this result “a shocker...” and he is right. Hans von Storch calls Mann’s study “rubbish.” Both men are Staunch advocates of global warming. But Mann’s mistakes are considerable. But he will get tenure soon anyway.

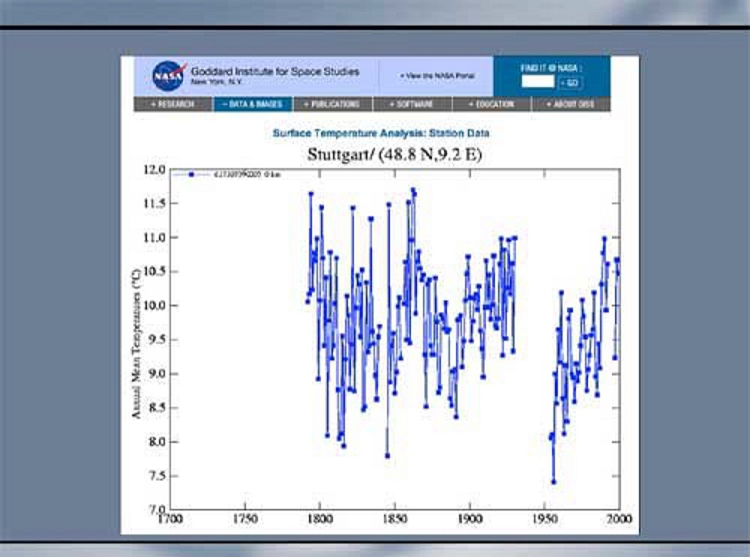

But the disrepute into which his study has fallen leaves us wondering just how much variation in climate is normal. Let’s look at a couple of stations.

Here you see that the current temperature rise, while distinctive, is far from unique. Paris was hotter in the 1750s and 1830s than today.

Similarly, if you look at Stuttgart from 1950 to present, it looks dramatic. If you look at the whole record, it is put into an entirely different perspective. And again, it was warmer in the 1800s than now.

Now, these are graphs taken from the GISS website at the time I did my research for the book. For those of you think the science is all aboveboard, you might contemplate this. The data have been changed.

I have no comment on why the Goddard Institute changed the data on their website. But it clearly makes the temperature record look more consistently upward-trending and more fearsome than it did a few months ago.

All right. With the second graph demolished, it is time to return to the first. Now we must ask, if surface temperatures have gone up in the twentieth century, what has caused the rise? Most people have been taught that the increase is caused by carbon dioxide, but that is by no means clear.

Two factors that were previously not of concern have recently come to the renewed attention of scientists. The first is the sun. In the past it was imagined that the effect of the sun was fairly constant and therefore any rise in temperature must be caused by some other factor. But it is now clear from work of scientists at the Max Planck institute in Germany that the sun is not constant, and is right now at a 1,000 year maximum. The data comes from sunspots.

According to Solanki and his associates:

This shows that solar radiation and surface temperature are correlated until recent times. Solanki says that the sun is insufficient to explain the current temperatures, and therefore another factor is also at work, presumably greenhouse gases. But the question is whether the sun accounts for a significant part of twentieth-century warming. Nobody is sure. But it is likely to be some amount greater than was previously thought.

Now we turn to cities:

Another factor that could change the record is heat from cities. This is called the urban heat bias, and as with solar effects, scientists tended to think the effect, while real, was relatively minor. That is why the IPCC allowed only six hundredths of a degree for urban heating. But cities are hot: the correction is likely to be much greater. We now understand that many cities are 7 or 8 degrees warmer than the Surrounding countryside.

(A temperature chart from a car driving around Berlin. The difference between city and country is 7 degrees.)

Some studies have suggested that the proper adjustment to the record needs to be four or five times greater than the IPCC allowance.

Now what does this mean to our record? Well remember, the total warming in the 20th century is six tenths of a degree.

If some of this is from land use and urban heating (and one studies suggests it is .35 C for the century), and some Is solar heating (.25 C for century), then the amount attributable to carbon dioxide becomes less. And let me repeat: nobody knows how much is attributable to carbon dioxide right now.

But if carbon dioxide is not the major factor, it may not make a lot of sense to try and limit it. There are many reasons to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels, and I support such a reduction. But global warming may not be a good or a primary reason.

So this is very important stuff. The uncertainties are great.

And now, we turn to the most important issue. WHAT WILL HAPPEN IN THE FUTURE?

To answer this, we must turn to the UN body known as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The IPCC, the gold Standard in climate science.

In the last ten years, the IPCC has published book after book. And I believe I may be the only person who has read them. I say that because if any journalist were to read these volumes with any care they would come away with the most extreme unease---and not in the way the texts intend.

The most recent volume is the Third Assessment Report, from 2001. It contains the most up-to-date views of scientists in the field. Let’s see what the text says. I will be reading aloud.

Sorry, but these books are written in academic-ese. They are hard to decipher, but we will do that.

Starting with the first section, The Climate System: An Overview, we turn to the first page of text, and on the third paragraph read:

Climate variations and change, caused by external forcings, may be partly predictable, particularly on the larger, continental and global, spatial scales. Because human activities, such as the emission of greenhouse gases or land-use change, do result in external forcing, it is believed that the large-scale aspects of human-induced climate change are also partly predictable. However the ability to actually do so is limited because we cannot accurately predict population change, economic change, technological development, and other relevant characteristics of future human activity. In practice, therefore, one has to rely on carefully constructed scenarios of human behaviour and determine climate projections on the basis of such scenarios.

Take these sentence by sentence, and translate into plain English. Starting with the first sentence. It’s really just saying:

Climate may be partly predictable.

Second sentence means:

We believe human-induced climate change is predictable.

Third sentence means:

But we can’t predict human behavior.

Fourth sentence:

Therefore we rely on “scenarios.”

The logic here is difficult to follow. What does “may be partly predictable” mean? Is it like a little bit pregnant? We see in two sentences we go from may be predictable to is predictable. And then, if we can’t make accurate predictions about population and development and technology... how can you make a carefully-constructed scenario? What does “carefully- constructed” mean if you can’t make accurate predictions about population and economic and other factors that are essential to the scenario?

The flow of illogic is stunning. Am I are making too much of this? Let’s look at another quote:

“The state of science at present is such that it is only possible to give illustrative examples of possible outcomes.”

llustrative examples. The estimates for even partial US compliance with Kyoto---a reduction of 3% below 1990 levels, not the required 7%---has been predicted to cost almost 300 billion dollars a year. Year after year. We can afford it. But if we are going to spend trillions of dollars, I would like to base that decision on something more Substantial than “illustrative examples.”

Let’s look at another quote.

My concerns deepen when I read “Climate models now have some skill in simulating changes in climate since 1850...” SOME SKILL? This is not skill in predicting the future. This is skill in reproducing the past. It doesn’t sound like these models really perform very well. It would be natural to ask how they are tested.

NEXT QUOTE

While we do not consider that the complexity of a climate model makes it impossible to ever prove such a model “false” in any absolute sense, it does make the task of evaluation extremely difficult and leaves room for a subjective component in any assessment.

Now, the term “subjective” ought to set off alarm bells in every person here. Science, by definition, is not subjective. I will point out to you that this is precisely the kind of issue that has Americans furious about the EPA. We know you can’t let a drug company manufacture a drug and also test it---that’s unreliable, and everybody knows it. So why in this high stakes climate issue do we allow the same person who makes a climate model to test it?

The flaws in this process are well known. James Madison, our fourth President:

No man its allowed to be judge in his own cause, because his interest would certainly bias his judgment, and not improbably, corrupt his integrity.

Madison is right.

Climate science needs some verification by outsiders.

NEXT QUOTE

Again, am I making too much of all this? It turns out I am not. Late in the text, we read:

“The long term prediction of future climate states Is not possible.”

Surely it should lead us to close the book at this point. If the system is non-linear and chaotic—and it is—then it can’t be predicted, and if it can’t be predicted, what are we doing here? Why are we worrying about the year 2100?

All right, you may be saying. Perhaps this is the state of climate science, as the IPCC itself tell us. Nevertheless we read every day about the dire consequences of global warming. What if I am wrong? What if a major temperature rise is really going to happen? Shouldn’t we act now and be safe? Don’t we have a responsibility to unborn generations to do so?

NEXT CHART - Act Now or Later?

Here is again the IPCC chart of predictions for 2100. As you see, they range from a low of 1.5 degrees to a high of 6 degrees. That is a 400% variation. It’s fine in academic research. Now let’s transfer this to the real world.

In the real world, a 400% uncertainty is so great that nobody acts on it. Ever.

If you planned to build a house and the builder said, it will cost somewhere between a million and a half and six million dollars, would you proceed? Of course not, you’d get a new builder. If you told your boss you were going on vacation and would be gone somewhere between 15 and 60 days, would he accept that? No, he’d say tell me exactly what day you will be back. Real world estimation has to be much, much better than 400%.

When all is said and done, Kyoto Is a giant global construction project. In the real world nobody builds with that much uncertainty.

Next, we must face facts about the present. If warming is a problem, we have no good technological solutions at this point. Everybody talks wind farms, but people hate them. They’re ugly and noisy and change the weather and chop birds and bats to pieces, and they are fought everywhere they are proposed. Here is the wind farm at Cape Cod, which has aroused everyone who lives there, including lots of environmentalists who are embarrassed but still..they don’t want them. Who can blame them? A very large anti-wind faction has grown up in England, partly because the government are trying to put farms in the Lake District and other scenic areas.

But whether we like the technology or not, do we really have the capability to meet the Kyoto Protocols? Reporting in Science magazine, a blue-ribbon group of scientists concluded that we do not:

So, if we don’t have good technology perhaps we should wait. And there are other reasons to wait. If in fact we are facing a really expensive construction job, we can afford it better later on. We will be richer. This is a 400 year trend.

Finally, I think it is important to recognize that we can adapt to the temperature changes that are being discussed. We are told that catastrophe will befall if we increase global temperature 2 degrees. But that is the difference in average temperature between New York and Washington DC. I don’t think most New Yorkers think a move to Washington is balmy. Similarly, a move to San Diego is an increase of 9 degrees.

Of course this is not a fair comparison, because a local change is not the same as a global change. But it ought at least to alert you to the possibility that perhaps things are not as dire as we are being told. And were told thirty years ago, about the ice age.

Last, I want you to think about what it means to say that we are going to act now to address something 100 years from now. People say this with confidence; we hear that the people of the future will condemn us if we don’t act. But is that true?

We’re at the start of the 21st century, looking ahead. We’re just like someone in 1900, thinking about the year 2000. Could someone in 1900 have helped us?

Here is Teddy Roosevelt, a major environmental figure from 1900. These are some of the words that he does not know the meaning of:

|

|

|

|

Given all those changes, is there anything Teddy could have done in 1900 to help us? And aren’t we in his position right now, with regard to 2100?

Think how incredibly the world has changed in 100 years. It will change vastly more in the next century. A hundred years ago there were no airplanes and almost no cars. Do you really believe that 100 years from now we will still be burning fossil fuels and driving around in cars and airplanes?

The idea of spending trillions on the future is only sensible if you totally lack any historical sense, and any imagination about the future.

If we should not spend our money on Kyoto, what should we do instead? I will argue three points.

First, we need to establish 21st century policy mechanisms. I want to return to those pages from the IPCC. The fact is if we required the same standard of information from climate scientists that we do from drug companies, the whole debate on global warming would be long over. We wouldn't be talking about it. We need mechanisms to insure a much, much higher standard of reliability in information in the future.

Second, we need to deal correctly with complexity of non-linear systems. The environment is a complex system, a term that has a specific meaning in science. Beyond being complicated, it means that interacting parts that modify each other have the capacity to change the output of the system in unexpected ways. This fact has several ramifications. The first is that the old notion of the balance of nature is thoroughly discredited. There is no balance of nature. To think so is to share an agreeable fantasy with the ancient Greeks. But it is also a shocking change for us, and we resist it. Some now talk of “balance in nature,” as a way to keep the old idea alive. Some claim there are multiple equilibrium states, but this is just a way of pretending that the balance can attained in different ways. It is a misstatement of the truth. The natural system of inherently chaotic, major disruption is the rule not the exception, and if we are to manage the system we are going to have to be actively involved.

This represents a revision of the role of mankind in nature, and a revision of the perception of nature as something untouched. We now know that nature has never been untouched. The first white visitors to the New World didn’t understand what they were looking at. In California, Indians burned old growth forest with such regularity that there is more old growth today than there was in 1850. Yellowstone was a beauty spot precisely because the Indians hunted the elk and moose to the edge of extinction. When they were prevented from hunting in their traditional grounds, Yellowstone began its complex decline.

We now have research to help us formulate strategies for management of complex systems. But! am not sure we have organizations capable of making these changes. I would also remind you that to properly manage what we call wilderness is going to be stupefyingly expensive. Good wilderness is expensive!

Finally, and most important—we can’t predict the future, but we can know the present. In the time we have been talking, 2,000 people have died in the third world. A child is orphaned by AIDS every 7 seconds. Fifty people die of waterborne disease every minute. This does not have to happen. We allow it.

What is wrong with us that we ignore this human misery and focus on events a hundred years from now? What must we do to awaken this phenomenally rich, spoiled and self-centered society to the issues of the wider world? The global crisis is not 100 years from now—it Is right now. We should be addressing it. But we are not. Instead, we cling to the reactionary and antihuman doctrines of outdated environmentalism and turn our backs to the cries of the dying and the starving and the diseased of our shared world.

And if we are going to remain too self-involved to care about the third world, can we at least care about our own? We live in a country where 40% of high school graduates are functionally illiterate. Where schoolchildren pass through metal detectors on the way to class. Where one child in four says they have seen a murdered person. Where millions of our fellow citizens have no health care, no decent education, no prospects for the future. If we really have trillions of dollars to spend, let us spend it on our fellow human beings. And let us spend it now. And not on our impossible fantasies of what may happen one hundred years from now.

Thank you very much.