The Personal Website of Mark W. Dawson

Containing His Articles, Observations, Thoughts, Meanderings,

and some would say Wisdom (and some would say not).

Reasoning

In my Chirps and Articles have often written about being rational and reasonable. I, therefore, have written two articles on these topics - “Rationality” and "Reasoning", with this article being the latter topic. To properly reason, you need to understand the Structure of the Reasoning, Formal and Informal Logic, Logical Fallacies, Cognitive Biases, and Common Sense. These must always be ascertained and incorporated for a reasonable debate to occur. You must also be aware of how to utilize common sense appropriately. Below is an outline of the Structure, Formal and Informal Logic, Logical Fallacies, Cognitive Biases, and Common Sense needed for proper Reasoning.

Structure

The structure of the Reasoning is very important to understand the validity of the Reasoning. A reasoning that is unstructured is difficult to evaluate and thus difficult to accept the conclusion. It is the responsibility of the person stating the Reasoning to structure their Reasoning properly. Anyone who is unwilling or unable to do this deserves little attention, as they are exhibiting a lack of intelligent acumen that makes their conclusion untenable.

Premises

A Premise is a statement that is assumed to be true and from which a conclusion can be drawn. The Premise must be clearly stated and unambiguous for argumentation to be valid. Often, premises are implicit or hidden in an argument. This means they are not mentioned but are assumed – either knowingly or unknowingly – by the speaker or writer. Hidden premises must be revealed to determine the validity of the arguments and conclusion. A false premise is an incorrect proposition that forms the basis of an argument. Since the false Premise (proposition or assumption) is not correct, the conclusion drawn will often be in error.

When listening or reading to Reasoning, or speaking or writing your Reasoning, the first thing you should do is examine the Premise. If the Premise can be factually challenged, or there are hidden premises that are invalid, then no amount of argumentation, nor the conclusion being drawn, is valid. Indeed, it is not even worth considering the arguments or conclusions if the Premise(s) are hidden or false.

Arguments

An Argument is a fact or assertion offered as evidence that the Premise is true. The logical validity of an argument is a function of its internal consistency, not the truth value of its premises. Argumentation is often based on informal logic and just as often contains Logical Fallacies and Cognitive Biases (discussed below). These Logical Fallacies and Cognitive Biases must be exposed to determine the validity of the argument. Also, arguments often contain both explicit or hidden premises that must be exposed and perhaps challenged for the argument to be valid. You should also be wary of common-sense arguments, as Common Sense is often not common or sensible (discussed below). A good Argument will also contain contravening arguments and a refutation of these contravening arguments. Without addressing contravening arguments, the argument is susceptible to refutation. This lack of contravening arguments often demonstrates the Cognitive Biases of the person presenting the Reasoning.

Conclusions

A Conclusion is the proposition arrived at by the logical Reasoning of the Premises and Arguments. Therefore, a conclusion that is not based on the arguments or only partially supported by the Premises and Arguments is not a valid conclusion. Consequently, you should carefully examine the conclusion to determine if the Premises and Arguments support the conclusion. Many times, the conclusion will slip in a premise which invalidates the Reasoning. It is fine to critique the conclusion based on the Premises and Arguments, or contravening arguments, so long as the critique is reasoned based. Criticizing a conclusion based upon an emotional appeal is not acceptable Reasoning and does not invalidate the conclusion.

Formal and Informal Logic

Logic, in general, can be divided into Formal Logic, Informal Logic, Symbolic Logic, and Mathematical Logic as outlined on the website, "The Basic of Philosophy - Logic". Logical systems should have three things: consistency (which means that none of the theorems of the system contradict one another); soundness (which means that the system's rules of proof will never allow a false inference from a true premise); and completeness (which means that there are no true sentences in the system that cannot, at least in principle, be proved in the system).

Formal Logic is what we think of as traditional logic or philosophical logic, namely the study of inference with purely formal and explicit content (i.e., it can be expressed as a particular application of a wholly abstract rule), such as the rules of formal logic that have come down to us from Aristotle. Formal Logic fallacies are errors in logic that are due entirely to the structure of the argument, without concern for the content of the premises. We can refer to all formal fallacies as Non-Sequiturs. Aristotle held that the basis for all formal fallacies was the non sequitur, which is why the term is known in Latin as Ignoratio elench - or ignorance of logic. Formal Logic is also the basis for all computer processing. If in your reasoning your Formal Logic is wrong, then your conclusion will be wrong.

Informal Logic is a recent discipline which studies natural language arguments and attempts to develop a logic to assess, analyze and improve ordinary language (or "every day") reasoning. Informal Logic fallacies occur when the "reasoning" or rationale behind the specific content of a premise is illogical - i.e., the support for the argument relies on rhetoric (appeals to emotion). While these arguments also possess a particular form, one cannot tell from the form alone that the argument is fallacious. This fallacy is most often the case when you have a Logical Fallacy or Cognitive Bias in your reasoning.

Symbolic Logic is the study of symbolic abstractions that capture the formal features of logical inference. It deals with the relations of symbols to each other, often using complex mathematical calculus, in an attempt to solve intractable problems traditional formal logic is not able to address.

Mathematical Logic is the application of the techniques of formal logic to mathematics and mathematical reasoning and, conversely, the application of mathematical techniques to the representation and analysis of formal logic.

Logical Fallacies

Most people are mostly ignorant about logical fallacies. A logical fallacy is a flaw in reasoning. Logical fallacies are like tricks or illusions of thought, and they're often very sneakily used by politicians and the media to fool people. You should visit the Wikipedia article that lists logical fallacies:

Examples of logical fallacies are:

Argument from Ignorance, also known as appeal to ignorance (in which ignorance represents "a lack of contrary evidence"), is a fallacy in informal logic. It asserts that a proposition is true because it has not yet been proven false (or vice versa). This represents a type of false dichotomy in that it excludes a third option, which is that there may have been an insufficient investigation, and therefore there is insufficient information to prove the proposition be either true or false. Nor does it allow the admission that the choices may, in fact, not be two (true or false), but maybe as many as four.

- True

- False

- Unknown between true or false

- Being unknowable (among the first three).

In debates, appeals to ignorance are sometimes used in an attempt to shift the burden of proof.

The following examples are from Philosophy Terms:

- Appeal to popular opinion

In an argument, have you ever heard someone say “everyone knows” or “9 out of 10 Americans agree”? This is an appeal to popular opinion, and it’s a major logical fallacy. After all, the world is full of popular misconceptions. For example, most Americans believe that Columbus proved the world was round, but actually, this is wrong. That had already been proven thousands of years earlier by the Egyptians, and no educated person in Columbus’ time believed the world was flat.

An appeal to popular opinion is very different from an appeal to expert opinion. If 99 out of 100 geologists agree that earthquakes are caused by tectonic plates, then that’s almost certainly true because the geologists are experts on the cause of earthquakes. However, the geologists are not experts on Korean history, so we shouldn’t appeal to their opinions on that subject. And the majority of people are not experts on anything other than their own lives and cultures, which means we should only trust popular opinion when those are the subjects at hand. Popular opinion is a fallacious argument; expert opinion is not. - Ad hominem attack

This is when you attack your opponent as a human being rather than dealing with their arguments. For example: “Einstein here says space-time is a continuum, but he’s a creepy little weirdo with awful hair, so he must be wrong!” - False dichotomy (A.K.A. False choice or false binary)

Sometimes a person will present two possible options and argue that we need to choose between them. But this assumes that there is no third option, and that might not be true. For example:

“Either we suppress protesters violently, or there will be chaos in the streets.”

In most cases, such a choice is fallacious: There will be moderate, careful ways to keep the public safe from chaos without any need for violent suppression. - Non sequitur

This is when you draw a conclusion that doesn’t follow logically from the evidence. Sometimes it’s very obvious: “I own a cat; therefore, I work as a computer programmer.” It’s easy to see that the evidence (the pet) doesn’t match the conclusion (the job). However, sometimes the non sequitur is quite subtle, as in the reductio ad hitlerum. - Reductio ad hitlerum

Despite its comical name, this is a real fallacy that you can see all the time in news media and political debates. A variety of non sequitur, it basically looks like this:

- Hitler was evil.

- Hitler did x.

- Therefore, x is evil.

On its surface, the reductio ad hitlerum can look appealing, and it often persuades people. But think about it: Hitler did many horrible things, but not everything Hitler did was evil. Let’s try filling in the blanks:

- Hitler was a vegetarian.

Therefore, vegetarianism is evil. - Hitler had a mustache.

Therefore, mustaches are evil. - Hitler was a carbon-based life form.

Therefore, carbon-based life forms are evil.

Clearly, this line of reasoning doesn’t work at all.

It is very important to understand logical fallacies when examining an issue, as not understanding logical fallacies can lead you to an improper conclusion. And many advocates of a public policy position utilize logical fallacies to gain your support.

Don't be fooled! – Understand Logical Fallacies

For more information on logical fallacies, I would recommend the book Mastering Logical Fallacies by Michael Withey. The following charts that encapsulate the major logical fallacies should be kept in mind when analyzing an argument (from Your Logical Fallacies).

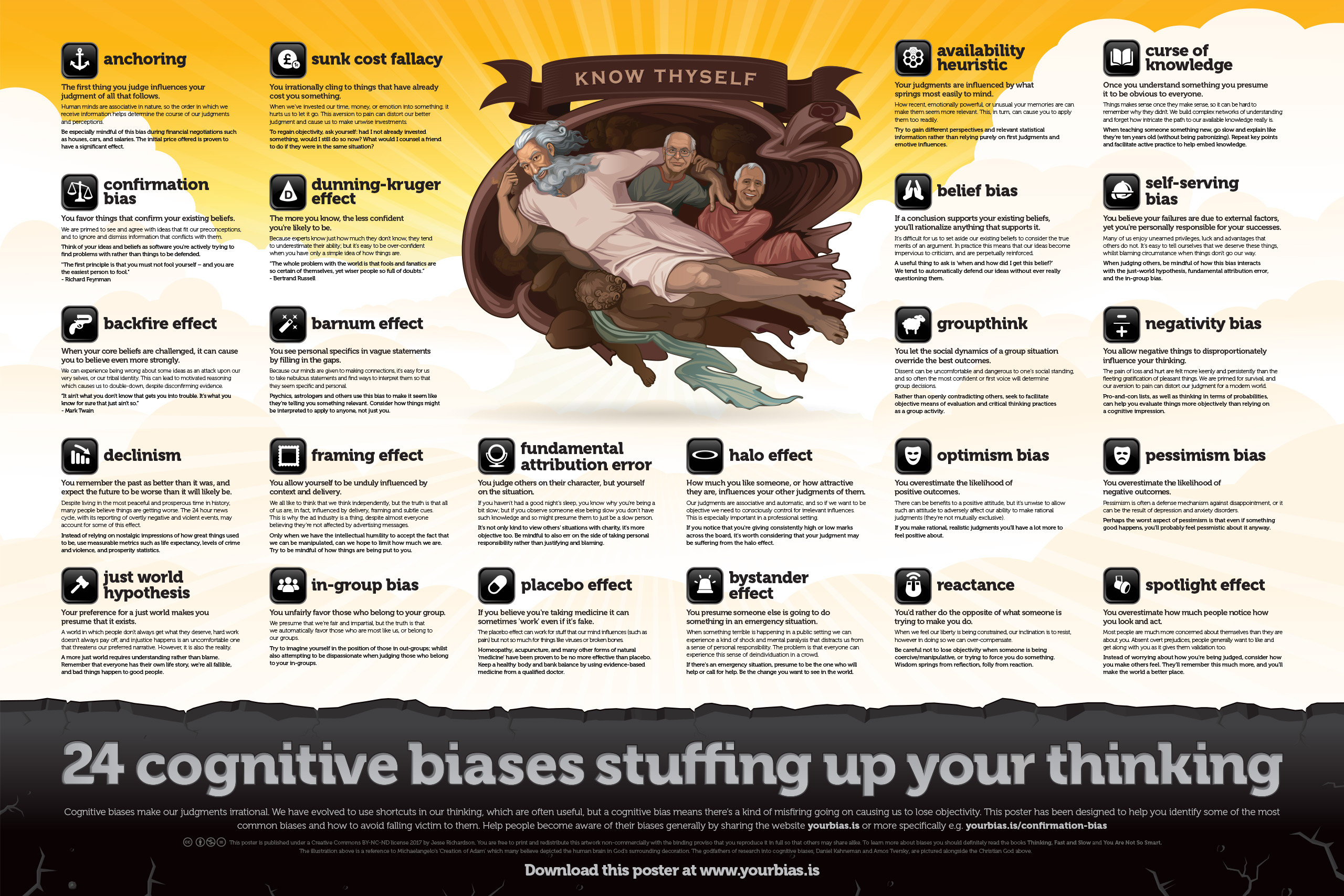

Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases are tendencies to think in certain ways that can lead to systematic deviations from a standard of rationality or good judgment and are often studied in psychology and behavioral economics. They are inherent in all forms of dialog and debate. You should be aware of cognitive biases in your own thoughts, as well as the opinions of others, as this will allow you to reach a more rational opinion. You should visit the Wikipedia article that lists Cognitive Biases.

What are Cognitive Biases?

Cognitive Bias is an umbrella term that refers to the systematic ways in which the context and framing of information influence individuals’ judgment and decision-making. There are many kinds of cognitive biases that influence individuals differently, but their common characteristic is that—in step with human individuality—they lead to judgment and decision-making that deviates from rational objectivity.

In some cases, cognitive biases make our thinking and decision-making faster and more efficient. The reason is that we do not stop to consider all available information, as our thoughts proceed down some channels instead of others. In other cases, however, cognitive biases can lead to errors for exactly the same reason. An example is confirmation bias, where we tend to favor information that reinforces or confirms our pre-existing beliefs. For instance, if we believe that planes are dangerous, a handful of stories about plane crashes tend to be more memorable than millions of stories about safe, successful flights. Thus, the prospect of air travel equates to an avoidable risk of doom for a person inclined to think in this way, regardless of how much time has passed without news of an air catastrophe.

Types of Cognitive Bias

There are hundreds of cognitive biases out there – way more than we could ever explore in a short article. The following list includes just ten Cognitive Biases chosen because they are either especially common or especially interesting. (this list is extracted from the website Philosophy Terms).

Anchoring Bias - The tendency to focus too much on a single piece of information rather than all information; this usually happens with either the first piece of information you received, the most recent information you received, or the most emotional information you received.

Availability Heuristic - The tendency to attach too much weight to information that we happen to have available to us, even if we’ve done no systematic research. For example, people tend to believe that their personal anecdotes are evidence of how the world works. If your cousin’s child developed autism after going through a standard round of vaccinations, you might believe that vaccinations cause autism even though science has conclusively shown that they don’t.

Bandwagoning - The tendency to adopt the same beliefs as the people around you or to assume that other people are making the right decision. If you live in a city with a subway, you may have seen bandwagoning at work – sometimes, a long line will form at one turnstile while the one next to it is completely free. Each new person shows up and just assumes that the second turnstile is broken, or else why would there be this disparity in the lines? But if no one decides to test this assumption, then the line will get longer and longer for no good reason!

Confirmation Bias - One of the most important cognitive biases! This is a tendency to find evidence that supports what you already believe – or to interpret the evidence as supporting what you already believe. Changing your viewpoint is hard cognitive work, and our brains have a tendency to avoid doing it whenever possible, even when the evidence is stacked against us!

Dunning-Krueger Effect - Less competent people have a tendency to believe that they know more than they actually do. Well-informed people usually have very low confidence in their own views because they know enough to realize how complicated the world is. People that are not well informed are extremely confident that their views are correct because they haven’t learned enough to see the problems with those views. This is what Socrates meant when he said that true wisdom was “to know that I know nothing.”

Fundamental Attribution Error - The tendency to believe that your own successes are due to effort and innate talent, while others’ successes are due to luck. Conversely, it’s also the tendency to believe that your own failures are due to bad luck, while other people’s failures are due to lack of effort and talent. Basically, it means you give yourself credit while denying credit to others. This bias has broad effects on cross-cultural encounters.

Halo Effect - The tendency to perceive a person’s attributes as covering more areas than they actually do. For example, if we know that a person has one type of intelligence (say good at math), we tend to expect that they will show other kinds of intelligence as well (e.g., knowledge of history).

Mood-Congruent Memory Bias - The tendency to recall information that fits our current mood or to interpret memories through that lens. When in a foul mood, we easily recall bad memories and interpret neutral memories as though they were bad. This leads to a tendency to think that the world is a sad, happy, or angry place when really it is only our mood.

Outcome Bias - The tendency to evaluate a choice on the basis of its outcome rather than on the basis of what information was available at the time. For example, a family may decide to send their child to an expensive college based on good financial information available at the time. However, if the family later falls into financial hardship due to unforeseen circumstances, this decision will appear, in retrospect, to have been excessively risky and a bad choice overall.

Pro-Innovation or Anti-Innovation Bias - The tendency to believe something is good (or bad) simply because it’s new. In Western society, we tend to overvalue innovation, while other societies (and many sub-cultures within the West, such as religious fundamentalists) overvalue tradition. Both biases are irrational: just because something is new or old doesn’t mean it’s going to be more or less beneficial. When we evaluate ideas, we should do it on the basis of their own merits, not simply how new or old the idea is.

Why We Have Cognitive Bias

According to Buster Benson's "Cognitive Bias Cheat Sheet", every cognitive bias is there for a reason - primarily to save our brains time or energy. If you look at them by the problem they’re trying to solve, it becomes a lot easier to understand why they exist, how they’re useful, and the trade-offs (and resulting mental errors) that they introduce.

- Too much information. As there is just too much information in the world, we have no choice but to filter almost all of it out. Our brain uses a few simple tricks to pick out the bits of information that are most likely going to be useful in some way.

- Not enough meaning. The world is very confusing, and we end up only seeing a tiny sliver of it, but we need to make some sense of it in order to survive. Once the reduced stream of information comes in, we connect the dots, fill in the gaps with stuff we already think we know, and update our mental models of the world.

- Need to act fast. We’re constrained by time and information, and yet we can’t let that paralyze us. Without the ability to act fast in the face of uncertainty, we surely would have perished as a species long ago. With every piece of new information, we need to do our best to assess our ability to affect the situation, apply it to decisions, simulate the future to predict what might happen next, and otherwise act on our new insight.

- What should we remember? There’s too much information in the universe. We can only afford to keep around the bits that are most likely to prove useful in the future. We need to make constant bets and trade-offs around what we try to remember and what we forget. For example, we prefer generalizations over specifics because they take up less space. When there are lots of irreducible details, we pick out a few standout items to save and discard the rest. What we save here is what is most likely to inform our filters related to problem 1’s information overload, as well as inform what comes to mind during the processes mentioned in problem two around filling in incomplete information. It’s all self-reinforcing.

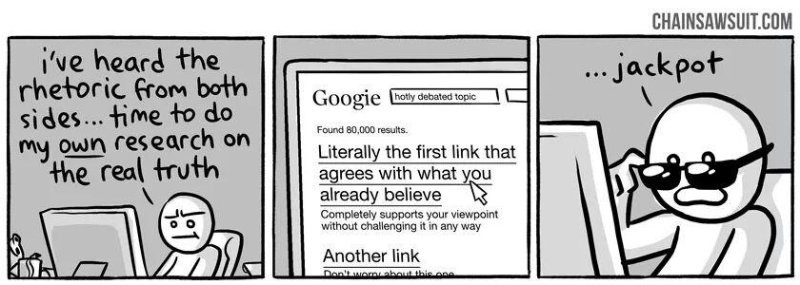

For more information on these items, please review Buster Benson’s article on this subject. For now, I will leave you with an amusing cartoon of Kris Straub that sums up the importance of understanding Cognitive Bias.

Don't be fooled! – Understand Cognitive Biases

For more information on cognitive biases, I would recommend the book; “Mindfields: How cognitive biases confuse our thinking in politics and life” by Mr. Burt Webb. The following charts that encapsulate the major cognitive biases should be kept in mind when analyzing an argument (from Your Bias):

Common Sense

I have mentioned applying common sense to these observations, but common sense can lead you astray. What most people mean by “Common Sense” is common knowledge and sensible responses. But common knowledge may not be so common amongst many people, or sensible responses may differ among reasonable people.

Common Sense also has the problems of circular reasoning, social influences, uncommon sense, and various other sociological problems, as well as Logical Fallacies & Cognitive Biases. A very good book that explains these problems, and the problems of utilizing common sense, is “Everything Is Obvious – How Common Sense Fails Us” by Duncan J. Watts.

Common knowledge is not so common as each person has a different breadth and depth of knowledge. The knowledge, education, and experience of each person differ. As such, each person may reach a different conclusion from another person. This does not necessarily make someone wrong if they disagree with you. Most often, if you politely discuss the disagreement, you may often come to a common agreement, or modify your or the other opinion, or simply agree to disagree. But you should always keep in mind that you may be wrong and be open to changing your conclusion.

Sensible responses are different amongst people, as each person has their own priorities and judgments of the importance of an issue. Sometimes people place more importance on their personal goals, while others may place more importance on social goals. And even within the goals, there are different priorities. They weigh the criteria to determine the sensible response, with each person putting different weights on each criterion, and then have a sensible response based on their criteria, which may (and possibly will) be different than another person’s response. Until you discuss the criteria and weights, you cannot know the reason for the other person’s response. Therefore, do not be quick to judge another’s response as it may be perfectly reasonable from the perspective of the other person. Again, politely discussing the response will help you better understand the other person.

Common sense is most appropriate in our social interactions with each other. We grow up and learn how to treat each other (such as politeness and common courtesies) within our cultural norms. This is one of the best purposes of common sense, and indeed we could not function as a society without this type of common sense. So, what do I mean by common sense?

My personal usage of common sense is to utilize human nature, our cultural norms, obtain as much knowledge on my own as reasonable, pay attention to the knowledge, education, experience, reasoning, and criteria of others (especially those that I may disagree with), and apply formal and informal logic to reach my own conclusions. I also allow for the possibility that I may be wrong and try to determine the consequences of my being right or wrong to reach what I consider a reasonable conclusion. It is on this basis that I have written these observations.

In Conclusion

Being reasonable requires that you put aside your biases and prejudices and dispassionately analyze the facts, and properly reason to reach a conclusion. However, reasoning is insufficient to reach the best decision, as the best decision requires that you apply “Rationality” to your reasoning. When the rational and reasonable conclusions you reach disagree with your preconceived biases or prejudices, you should be prepared to change your opinion. Even when you have reached a rational and reasonable conclusion, you should be cognizant that you could be wrong. Or, as Benjamin Franklin has advised, “Doubt a little of your own infallibility.” Franklin also advised that when presented with evidence to the contrary of your conclusion that you should consider:

“For having lived long, I have

experienced many instances of being obliged by better information,

or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important

subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise.

It is therefore that the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt

my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of

others.”

- Benjamin Franklin

Advice that we should all take to heart and practice - to doubt our own infallibility and to change our mind upon acquiring better information or by giving fuller consideration to the topic at hand. I have found these pearls of wisdom very helpful throughout my life, and we all would be better persons and have a better society if all of us kept these pearls of wisdom in mind throughout our lives. After all, it is also the rational thing to do.

Further Readings

For more general information on Reasoning, I would suggest the website: Essential Thinking for Philosophy - a website of critical thinking activities for students. The book "A Rulebook for Arguments 5th Edition" by Anthony Weston is the ultimate 'how-to' book for anyone who wants to use reasons and evidence in support of conclusions, to be clear instead of confusing, persuasive instead of dogmatic, and better at evaluating the arguments of others. The book "Thinking Through Questions: A Concise Invitation to Critical, Expansive, and Philosophical Inquiry Concise Edition" by Anthony Weston and Stephen Bloch-Schulman is an accessible and compact guide to the art of questioning, covering both the use and abuse of questions. The book "Informal Logic: A Handbook for Critical Argumentation" by Douglas N. Walton is a more extensive text on argumentation.