The Personal Website of Mark W. Dawson

Containing His

Articles, Observations, Thoughts, Meanderings,

and some would say Wisdom (and some would say not).

The Four Forces of Nature

In my Science Article “The Fundamental Properties and Constants of the Universe” I explore the universal fundamentals of science. In this article I will briefly explore the four forces in the Universe known to science; Gravity, Electromagnetism, and the Strong and Weak Atomic forces. These four forces are explained in the Wikipedia articles below:

GravityGravity (from Latin gravitas, meaning 'weight'), or gravitation, is a natural phenomenon by which all things with mass or energy—including planets, stars, galaxies, and even light—are brought toward (or gravitate toward) one another. On Earth, gravity gives weight to physical objects, and the Moon's gravity causes the ocean tides. The gravitational attraction of the original gaseous matter present in the Universe caused it to begin coalescing, forming stars—and for the stars to group together into galaxies—so gravity is responsible for many of the large-scale structures in the Universe. Gravity has an infinite range, although its effects become increasingly weaker on farther objects. Gravity is most accurately described by the general theory of relativity (proposed by Albert Einstein in 1915) which describes gravity not as a force, but as a consequence of the curvature of spacetime caused by the uneven distribution of mass. The most extreme example of this curvature of spacetime is a black hole, from which nothing—not even light—can escape once past the black hole's event horizon. However, for most applications, gravity is well approximated by Newton's law of universal gravitation, which describes gravity as a force which causes any two bodies to be attracted to each other, with the force proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them. Gravity is the weakest of the four fundamental interactions of physics, approximately 1038 times weaker than the strong interaction, 1036 times weaker than the electromagnetic force and 1029 times weaker than the weak interaction. As a consequence, it has no significant influence at the level of subatomic particles. In contrast, it is the dominant interaction at the macroscopic scale, and is the cause of the formation, shape and trajectory (orbit) of astronomical bodies. |

ElectromagnetismElectromagnetism is a branch of physics involving the study of the electromagnetic force, a type of physical interaction that occurs between electrically charged particles. The electromagnetic force is carried by electromagnetic fields composed of electric fields and magnetic fields, and it is responsible for electromagnetic radiation such as light. It is one of the four fundamental interactions (commonly called forces) in nature, together with the strong interaction, the weak interaction, and gravitation. At high energy the weak force and electromagnetic force are unified as a single electroweak force. Lightning is an electrostatic discharge that travels between two charged regions. Electromagnetic phenomena are defined in terms of the electromagnetic force, sometimes called the Lorentz force, which includes both electricity and magnetism as different manifestations of the same phenomenon. The electromagnetic force plays a major role in determining the internal properties of most objects encountered in daily life. The electromagnetic attraction between atomic nuclei and their orbital electrons holds atoms together. Electromagnetic forces are responsible for the chemical bonds between atoms which create molecules, and intermolecular forces. The electromagnetic force governs all chemical processes, which arise from interactions between the electrons of neighboring atoms. There are numerous mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic field. In classical electrodynamics, electric fields are described as electric potential and electric current. In Faraday's law, magnetic fields are associated with electromagnetic induction and magnetism, and Maxwell's equations describe how electric and magnetic fields are generated and altered by each other and by charges and currents. The theoretical implications of electromagnetism, particularly the establishment of the speed of light based on properties of the "medium" of propagation (permeability and permittivity), led to the development of special relativity by Albert Einstein in 1905. |

Strong AtomicThe Nuclear force (or nucleon–nucleon interaction or residual strong force) is a force that acts between the protons and neutrons of atoms. Neutrons and protons, both nucleons, are affected by the nuclear force almost identically. Since protons have charge +1 e, they experience an electric force that tends to push them apart, but at short range the attractive nuclear force is strong enough to overcome the electromagnetic force. The nuclear force binds nucleons into atomic nuclei. The nuclear force is powerfully attractive between nucleons at distances of about 1 femtometre (fm, or 1.0 × 10-15 metres), but it rapidly decreases to insignificance at distances beyond about 2.5 fm. At distances less than 0.7 fm, the nuclear force becomes repulsive. This repulsive component is responsible for the physical size of nuclei, since the nucleons can come no closer than the force allows. By comparison, the size of an atom, measured in angstroms (Å, or 1.0 × 10-10 m), is five orders of magnitude larger. The nuclear force is not simple, however, since it depends on the nucleon spins, has a tensor component, and may depend on the relative momentum of the nucleons. In particle physics, Strong Interaction is the mechanism responsible for the strong nuclear force, and is one of the four known fundamental interactions, with the others being electromagnetism, the weak interaction, and gravitation. At the range of 10-15 m (1 femtometer), the strong force is approximately 137 times as strong as electromagnetism, a million times as strong as the weak interaction, and 1038 (100 undecillion) times as strong as gravitation. The strong nuclear force holds most ordinary matter together because it confines quarks into hadron particles such as the proton and neutron. In addition, the strong force binds these neutrons and protons to create atomic nuclei. Most of the mass of a common proton or neutron is the result of the strong force field energy; the individual quarks provide only about 1% of the mass of a proton. |

Weak AtomicIn particle physics, the Weak Interaction, which is also often called the weak force or weak nuclear force, is the mechanism of interaction between subatomic particles that is responsible for the radioactive decay of atoms. The weak interaction serves an essential role in nuclear fission, and the theory regarding it in terms of both its behavior and effects is sometimes called quantum flavordynamics (QFD). However, the term QFD is rarely used because the weak force is better understood in terms of electroweak theory (EWT). In addition to this, QFD is related to quantum chromodynamics (QCD), which deals with the strong interaction, and quantum electrodynamics (QED), which deals with the electromagnetic force. The effective range of the weak force is limited to subatomic distances, and is less than the diameter of a proton. It is one of the four known force-related fundamental interactions of nature, alongside the strong interaction, electromagnetism, and gravitation. |

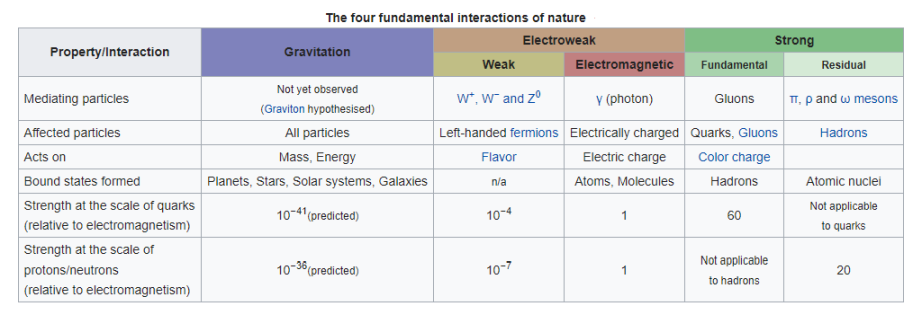

These forces interact with each of in the following manner:

Fundamental InteractionIn physics, the Fundamental interaction, also known as fundamental forces, are the interactions that do not appear to be reducible to more basic interactions. There are four fundamental interactions known to exist: the gravitational and electromagnetic interactions, which produce significant long-range forces whose effects can be seen directly in everyday life, and the strong and weak interactions, which produce forces at minuscule, subatomic distances and govern nuclear interactions. Some scientists hypothesize that a fifth force might exist, but the hypotheses remain speculative. Each of the known fundamental interactions can be described mathematically as a field. The gravitational force is attributed to the curvature of spacetime, described by Einstein's general theory of relativity. The other three are discrete quantum fields, and their interactions are mediated by elementary particles described by the Standard Model of particle physics. Within the Standard Model, the strong interaction is carried by a particle called the gluon, and is responsible for quarks binding together to form hadrons, such as protons and neutrons. As a residual effect, it creates the nuclear force that binds the latter particles to form atomic nuclei. The weak interaction is carried by particles called W and Z bosons, and also acts on the nucleus of atoms, mediating radioactive decay. The electromagnetic force, carried by the photon, creates electric and magnetic fields, which are responsible for the attraction between orbital electrons and atomic nuclei which holds atoms together, as well as chemical bonding and electromagnetic waves, including visible light, and forms the basis for electrical technology. Although the electromagnetic force is far stronger than gravity, it tends to cancel itself out within large objects, so over large distances (on the scale of planets and galaxies), gravity tends to be the dominant force. Many theoretical physicists believe these fundamental forces to be related and to become unified into a single force at very high energies on a minuscule scale, the Planck scale, but particle accelerators cannot produce the enormous energies required to experimentally probe this. Devising a common theoretical framework that would explain the relation between the forces in a single theory is perhaps the greatest goal of today's theoretical physicists. The weak and electromagnetic forces have already been unified with the electroweak theory of Sheldon Glashow, Abdus Salam, and Steven Weinberg for which they received the 1979 Nobel Prize in physics. Progress is currently being made in uniting the electroweak and strong fields within what is called a Grand Unified Theory (GUT). A bigger challenge is to find a way to quantize the gravitational field, resulting in a theory of quantum gravity (QG) which would unite gravity in a common theoretical framework with the other three forces. Some theories, notably string theory, seek both QG and GUT within one framework, unifying all four fundamental interactions along with mass generation within a theory of everything (ToE).

|

Therefore, in science when you are discussing “The Fundamental Properties and Constants of the Universe” and “The Four Forces of Nature” these are the only ones known to science. To paraphrase Chief Engineer Montgomery Scott in “Star Trek” - “You cannot violate the fundamental properties and constants of the Universe nor ignore the forces of nature”. For these items must be accounted for in any scientific theory, hypothesis, or discussion involving our Universe. They cannot be violated, compensated for, nor ignored. To do so is to invalidate any logical argument you may present. Just like the violation of the Laws of Thermodynamics leads to a rejection of a patent application, the violation of the Fundamental Properties and Constants and the Four Forces of Nature in the Universe leads to the rejection of any scientific theory, hypothesis, or discussion involving our Universe.

If you have any comments, concerns, critiques, or suggestions I can be reached at mwd@profitpages.com.

I will review reasoned and intellectual correspondence, and it is possible that I can change my mind,

or at least update the content of this article.